Become a Storymaker

We all need to learn to become story makers. In a world where we are all content creators and publishers, it is our responsibility to become craftspeople in the art of story making, if we expect anyone to give a damn about what we are saying.

Every day we are telling stories, many of which are about seemingly mundane events in our lives.

Why do we all find such interest in these boring posts, updates, pictures and videos - posted about what we are eating, where we are traveling to, what our pets look like or who we are hanging out with? Because at the core we are all linked by some of the same basic human desires. And experiencing "stories" is a core human desire, not only for entertainment, but touching upon our basic survival instincts. By experiencing other people's stories, we seek to have a wider perspective on life and how to traverse it.

While we might think we are simply browsing mindless pictures of food or vacation shots, we are in fact satisfying a basic human urge to learn through stories. Woven throughout these constant streams of content (social media) and even more intentional content (blog posts, professional photography, videos, movies, books, etc.), are common threads and core emotions. By understanding why we all need stories in our lives, and also understanding why stories make us human, we can hopefully become better at making and telling stories in our own lives.

Today, more than ever before in the history of modern civilization, individuals are empowered with the tools to be story tellers and the technology to see their stories spread far and wide in the blink of an eye.

The web and the technology that connects us all has turned our world into a world of stories. We experience them in short bursts of a Twitter update or an Instagram photo, we experience them on Vine or through blogs, and we come in contact with "content" created by other people for our consumption at an almost constant rate. When we aren't consuming, we are creating and publishing for others.

When, in your day to day life, are you free from the content of others?

When are you simply existing in the moment? Not publishing, not sharing, not using some aspect of the web or technology to consume or publish information? It's kind of amazing when you think about it, and then compare it to your daily life 20 years ago. If you're as old as I am or older, you will recall a very different daily experience. I'm not saying that this is a bad change. What I am saying is that we owe it to ourselves to try to become better at telling these stories and putting out this content if we want it to matter. And for those of us for whom this is a job (writers, content strategists, photographers, videographers, creative directors, art directors, web designers, etc.), learning to become better at these things should help us to be better at our jobs.

At the end of the day, everything is about the story.

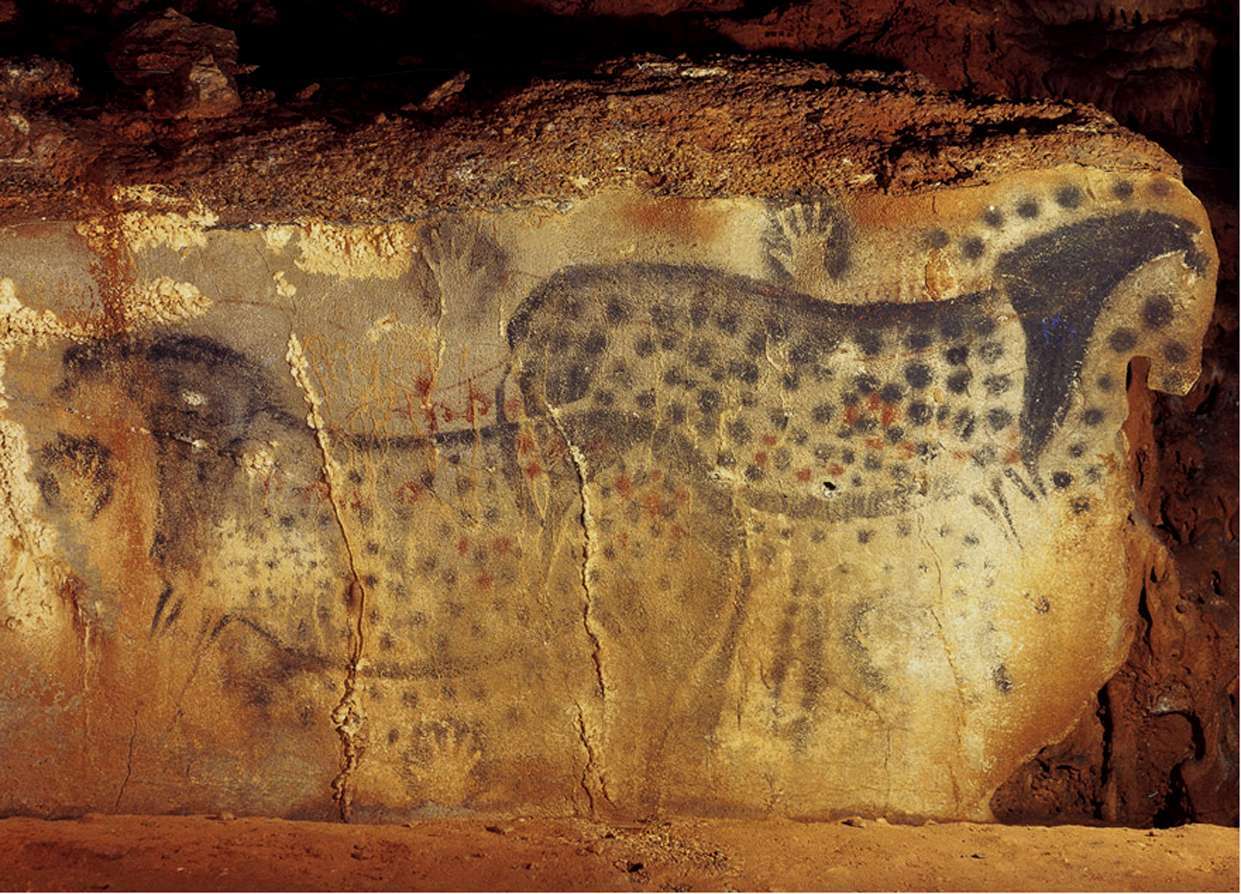

Let's back up about 30,000 years so I can make a point.

We started out as an evolving creature using stories to not only help us survive, but to create the culture that would eventually define us from all other creatures sharing this big rock. Storytelling was the key to what made us "human". Through the telling of stories, we not only helped ourselves understand the world around us, but we left a record of our very existence. We used images to tell these stories, much earlier than we developed written language or even advanced verbal communication skills.

Somehow, communicating with images is almost instinctual for humans.

It is particularly fascinating that in certain caves where early paintings have been located, scientists have determined that several thousand years may have passed between the first set of drawings and another set; yet the visual language and imagery remained almost identical. This might lead one to conclude that communicating visually is a basic human instinct and not something that has to be learned or taught in order to hold value and contain consistent attributes. If you have never taken the time to really explore the cave paintings of Lascaux, I encourage you to visit this site and prepare to have your mind blown.

Remember when everyone was freaking out about Facebook buying Instagram for 1 Billion dollars?

Yes you remember. Well, while we can definitely agree that Instagram was grabbing the lion's share of tweeners and other juicy users at an blazingly fast rate, there was something else there in what Facebook was buying. Facebook - which I'm sure you can agree has become a shitstorm of political rants, spam, pictures of children with horrible deformities guilt-tripping you into hitting the "like" button and other useless and often incorrect information - is dying. It is dying because it has become overrun with all the crap that takes away from what we, as users, as humans, are looking for and looking to do.

We are looking for stories; and Instagram with its single image and short caption does a much better job at letting us experience stories than Facebook does with all its junk, clutter and regurgitated jokes or memes.

Facebook bought what it might see as a lifesaver, because even the people at Facebook understand that as humans, we will never stop needing to experience stories - and tell our own. And images, simple still images, are the most primitive and human way to do just that.

We can all agree that stories are a key component to our human-ness. Both the desire to tell them, and to experience them - through images, words, spoken word, art, dance, song, poetry, etc.

Which would lead us to think we would have gotten pretty good at story telling then, right? Well I've spent some time looking around at what the people around me are "creating" on all the networks we now have at our disposal for publishing stories at an amazingly fast pace, to an ever widening audience - and guess what - it stinks.

Generally, we suck at telling good stories.

Don't fear, you're not a lost cause though, because if you think back to your childhood, you were probably a very good story maker.

How many of you had imaginary friends? Or crafted elaborate tales around the origins of the swing set? Or faced death on a daily basis in the backyard with your squirt gun? I am often reminded by my parents, who still find enjoyment in the fact, that I had an imaginary friend named Tur-shi-sho, and he had a pet dog named Mupp. They would come to dinner often (we had to set place settings for Tur-shi-sho, and Mupp would lay at his feet at the table), I worried about them when it stormed, and generally felt about them as I did about the real world, because they were each a part of my stories.

We are naturals at this, if we only let go of the constraints we've been taught and the fear of being overly dramatic or specific in our story telling.

A really good story has an opinion, a perspective. We are not weather reporters announcing the temperature readings. At least, we shouldn't be if we want anyone to tune in.

Remember when Twitter and blogs really started to take off?

Professional journalists were bitching because we started attributing value to user generated content, and immediacy, over trained reporting or journalism. This is the world we now live in, where we get so much "content" and inputs from so many sources. But when do we even stop to question the authority or "trusted source" for the things we are consuming? Wolf Blitzer won't get the scoop when we can count on the guy living next to Bin Laden to tweet about the choppers dropping off elite forces in his neighborhood.

This era of self-publishing and social networks has definitely impacted the way we consume and produce data, and we've barely had a chance to think about how it's impacted us as human beings.

Human beings, for thousands of years, relied on paintings, drawings, spoken word, poetry and epic tales written in early manuscripts to help us define the world we lived in and how we felt about it.

I've come to realize that most of my efforts at Fastspot, when boiled down, are really about helping our clients become better storymakers. Why? Because everything is a story. A brand is a story, a museum is a collection of many stories, a college is a place that allows people to create their own stories, a business is a place that often is selling a story to others. And with today's technologies and networks, we are all expected to be telling these stories. Which we are doing but in the most dismal ways imaginable because we were never taught to be story makers, or story tellers. We have to learn some new skills if we are expected to have our stories rise to the top, out of the increasingly overpopulated world we live and publish in.

What makes a good story, and how can you get better at making them and telling them?

I think it's important to recognize that every time you tell a story, you are re-creating it. Even the act of remembering the story is a creative process. The renowned author and neuroscientist Oliver Sacks has stated,

"We now know that memories are not fixed or frozen...but are transformed, disassembled, reassembled, and recategorized with every act of recollection."

And researcher Rosalind Cartwright reminds us in her fascinating book, The Twenty Four Hour Mind, that,

"Memory is never a precise duplicate of the original...it is a continuing act of creation."

Let the facts of science free you from the constraints of sticking to "just the facts ma'am". The entire notion is a fallacy. You, as the story teller, are the artist creating the story - every time you tell it.

Our brains are hard wired to seek out stories.

We actually get a chemical release that is triggered in the brain when we experience a fictional story. We prefer fiction because we like to live out situations vicariously through stories. Fiction allows our minds to live out ideas and situations which may never actually occur, in a way, preparing us better for an unknown future. This taps into our basic survival instincts.

Stories are also essentially the basis for most religions in the world.

This once again supports the premise that we not only seek out and enjoy stories, but we need them. They help provide us some comfort and understanding, just as they did for early man living in caves, about the world we live in and the unknowns we are faced with every day and throughout our lives. Harvey Cox, a highly regarded theologian stated,

"All humans have an innate need to hear and tell stories and to have a story to live by." (Harvey Cox, The Seduction of the Spirit).

These aren't trivial things we are talking about here, these stories we are asked to tell and publish in our daily lives, and I ask that we not forget how important they can be if we give them the proper focus and attention.

Start training yourself to look for the better story when you sit down to publish things.

It's easy to get lazy and replicate the nonsense we are bombarded with daily, but stop for a second before you post that next update to the website or Facebook, and think, am I telling a good story? People mistakenly think that a great story must come out of the occasion itself. For example, if you walked outside and a satellite fell from the sky and landed 10 feet from where you stood - you'd think you have a great story to tell. Or if your boring trip to the beach turned into a wild rescue attempt as you swam out to pull in a child stuck in a riptide, you'd have an amazing story to tell, right? Wrong. You'd just have a series of unusual events to talk about; whether they were good stories or not is up to you. How do you make them into great stories? Think about some of the best movies you've seen, or books you've read - were they all about epic unusual bizarre occurrences? No, probably not. Most likely they were simply well made stories that sucked you in. Stories that allowed your primitive human brain to enjoy living through someone else's eyes, in order to help you address core things that plague your inner primitive mind.

Think about the thing you are about to publish, and ask yourself, "Why?".

Many of us have heard UX professionals like Whitney Hess talk about the benefits of the 5 Whys.

The 5 Whys is a troubleshooting technique originally developed by Sakichi Toyoda and used within the Toyota Motor Corporation during the evolution of its manufacturing methodologies. It is a critical component of problem-solving training, delivered as part of the induction into the Toyota Production System. The architect of the Toyota Production System, Taiichi Ohno, described the 5 Whys method as "the basis of Toyota's scientific approach . . . by repeating why five times, the nature of the problem as well as its solution becomes clear."[2]

Let's look at a recent post a client had put into their website's main page, arguably a place for important and interesting stories to be placed.

They started out with this:

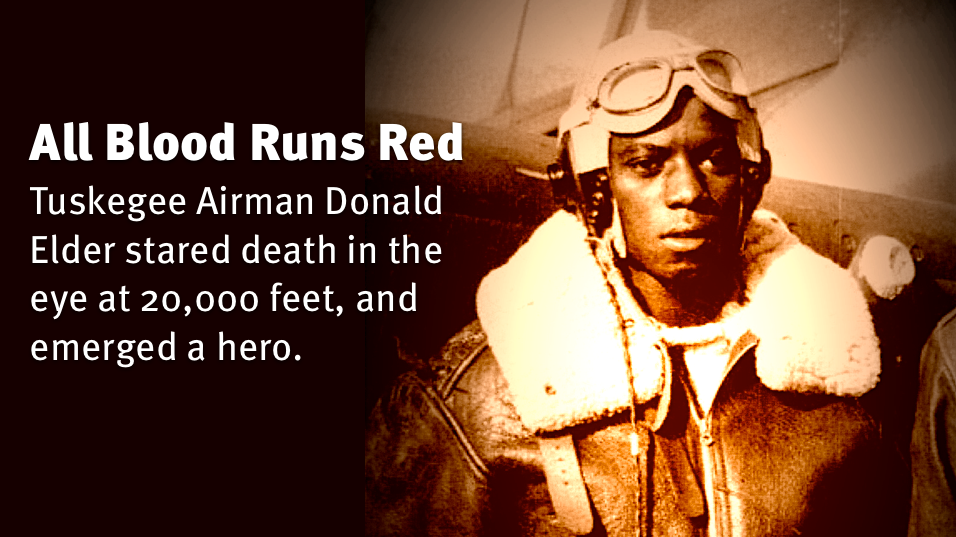

"Red Tails. Veterans of the Tuskegee Airmen will visit the "college name" to share their World War II combat experiences."

So here we have the ingredients to make a fascinating story, yet it's put out into the world in a pretty lackluster way - and it's not tapping into any of the basic human emotions we all are pre-programmed to respond to: Survival, death, fear, heroism, courage, good vs. evil.

Let's see if by applying the 5 whys, we get a more interesting starting place from which to make and tell this story.

- Why are they coming? Because it is important to remember the trials and tribulations of wars and those individuals who fought in them.

- Why? Because war is the ultimate human sacrifice and gives us the freedoms we enjoy today.

- Why? Because we must fight against the evil forces in the world that seek to overcome us.

- Why? Because eventually we will all die and we want to know we died fighting for good in our lives.

- Why? Because at our core, human beings are inherently good and moral and strive to exhibit this kind of behavior in the face of adversity.

Now here we have a much more interesting starting place if we are looking for the building blocks of our story.

We've gotten to some core human attributes - striving for good, facing fear, human equality.

And the story of the Tuskegee airmen is particularly poignant because these were African American soldiers risking their lives for a country that still didn't treat them as equals.

This story, if given an opportunity to be better "crafted" to not only include an image (because we now know how important images are!), but also a more interesting starting point - might look and read like this:

The best stories have the best specifics.

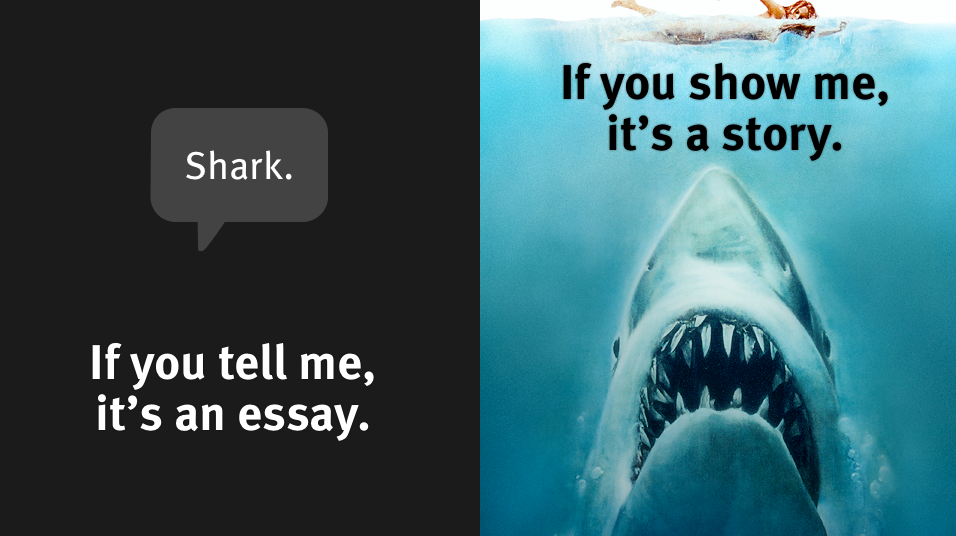

We aren't interested in generalizations. Yet it's our inclination to start out with a generalization and then move into the details. This is probably because we were taught in school to write more from an editorial perspective, not a storytelling one.

We want to show, not tell, when we make stories. So start with specifics, details and imagery.

Get to the root of the emotion, and catch your reader's eye by getting to the core issues of why the story matters in the first place.

You may say, OK Tracey, easily done with such an interesting story as the Tuskeegee airman, but how do I do that in my daily life. I went to Facebook and pulled the first post with an image that I saw. I wanted to see if I could apply the "Why?" formula to something completely mundane and get to something more interesting.

Here we go:

My friend posted to Facebook about how they were selling their old pickup truck that they've had for many years. There was a photo with a caption that said "Goodbye old friend." The status update above the photo read:

"So sad. 12 plus years later....Bought before kids! We will always have awesome fond memories of life with the Red Truck. Now on to new adventures with the Jeep! Here's to the next era!"

What happens to this story if we apply the Why technique? Let's see.

- Why are they saying goodbye to their old trusted friend Red Truck? Because they needed a new car.

- Why? Because the truck was old and didn't serve their needs anymore.

- Why? Because they have 2 kids now and loads more shit to carry around.

- Why? Because they are older now and their lives have changed.

- Why? Because everyone gets older and changes and eventually we all die.

Amazing what the "Why's" have revealed about this seemingly benign post about a truck. It is actually about death! Now I realize you could take this in many different ways, and I encourage you to do this as an exercise - where does your story end up, or find itself fit to start out at?

I know I've covered a lot in this post, and I hope it's given you food for thought.

We all want to be better story tellers, and we can be if we own the fact that we are the creative artist behind each story, each memory, each sharing of something between people.

I apologize for ending on a morbid post (although I believe that most stories are indeed about confronting the fear of death but that's for another post). I'm really curious how you strive to be a better story maker if you are someone who is responsible for publishing content? Do you have tricks of the trade that you can share? How do you combat the urge to crank out another boring press release formatted news post? How do you try to ensure your stories are being consumed, and are worth it?

I'm sure this post will inspire more, as it touches upon the foundation of what I do every day, and probably what many of you do every day as well. Until then - I look forward to your stories, and I hope you enjoyed mine.